AKY2K - Canoeing on the Noatak River, Alaska - August 2000

Adventure in Alaska!

© Don Childrey 2000

Tammy Dunn recently asked me if I would be interested in writing some articles about outdoor recreation for the Montgomery Herald. Although I had never considered writing for the paper before, it seemed like an interesting opportunity. As with most opportunities in life, you have to get up and walk through that open door to discover what's on the other side. So I accepted her challenge. This article kicks off a series on outdoor adventure that I hope we both find interesting and entertaining.

A few years ago, I would never have imagined myself paddling down a river in Alaska. But then some of my adventurous friends started talking about going to Alaska. We had already been enjoying canoe trips in North Carolina. Combining the two ideas sounded like fun, so we started making plans. Once you have a plan, turning an opportunity into reality becomes easier.

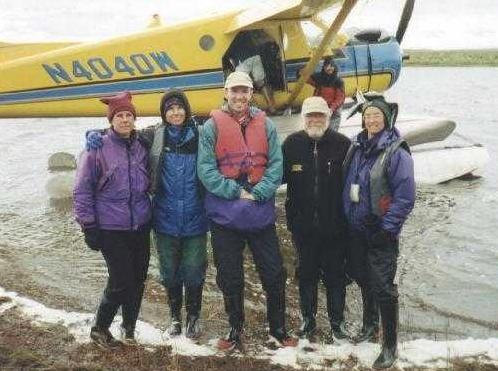

Two years of saving, researching, planning, and anticipation finally came together on August 4th as I headed off to the airport in Charlotte. Over the next two days, I met up with five other friends from NC. Our plan was to spend 12 days paddling 150 miles down the Noatak River, with extra time built in for day hikes and naps.

The river portion of our trip would start in the Gates of the Arctic National Park, located in northwestern Alaska. But the adventure started well before we arrived at the river.

The Noatak River has the largest watershed in North America still virtually untouched by human development. This river is so far out in the wilderness that getting to it requires a two hour float plane ride from the town of Bettles, AK.

Bettles is pretty far out too. There are no roads to this town of 54 people, unless you count the ice road that opens during the winter. We flew 300 miles on a 16-passenger plane from Fairbanks to Bettles.

The float plane ride from Bettles to the river was an exciting adventure in itself. Imagine landing a plane on a pond barely twice the size of the one in front of West Montgomery High!

When we finally reached the river, we were actually closer to mainland Russia than we were to Fairbanks. Which is exactly where we wanted to be. Right in the middle of 8 million acres of remote wilderness with three canoes, a river, and two weeks worth of food. No telephone, no TV, and ... no night.

At 100 miles north of the Arctic Circle, the August sun doesn't set until almost midnight and rises around 4 am. In between, the sun is just below the horizon, so the sky never really gets dark. It took us several days to get used to going to bed with the sun still shining.

Observing wildlife was a highlight of our trip. We quickly learned the Alaska wave. It's sort of like waving hello, making the Catholic sign of the cross, and having an epileptic attack, all at the same time. Otherwise the mosquitoes, who spend most of the year frozen and are really hungry when they're not, will cover your face, neck and anywhere else they can land unswatted.

Fortunately Alasquitoes are slow and soft. Unlike our own Asian Tiger mosquitoes, which come in fast and teeth first. A casual swat is usually enough to knock out the first wave of Alasquitoes and buy yourself a little time.

We were prepared for the mosquitoes. We had head nets and a screen tent with us. The screen tent allowed us to cook and eat without being confined in a head net.

It didn't take long to learn there are several things you should not do while wearing a head net. Taking a bite of a candy bar and sneezing are two major no-no's. Drinking from a water bottle through a head net isn't necessarily graceful, but it usually works.

The Noatak valley is home to grizzly bears as well as mosquitoes. Our defense against grizzlies was a can of cayenne pepper spray. The label said the squirt would last from 4 to 7 seconds and had a range of 10 to 15 feet. The label advised we stay upwind when using it. I wondered if the pepper spray would really be more of a seasoning for the bear's next meal than a deterrent to him eating me.

Early one morning my friend Trey crawled out of his tent with sleepy eyes to find the facilities. He stumbled towards the bushes at the back of the gravel bar we were camped on. The sound of his tent zipper brought me half way back from dreamland. His next words brought me the rest of the way.

"Hey Dad. (pause) There's something really big out here..." I couldn't get out of my sleeping bag and tent fast enough!

There are no trees in the Noatak valley, just scattered bushes about five feet high. In this spot, the bushes were close enough together to hide a big critter barely 15 feet away. By the time I got out there, it had moved off into the bushes. We could just see the top of its furry brown back over the bushes, but that was all.

We were really curious to see the rest of it, but smart enough not to move closer. I think it was curious too, because it could have just slipped away but didn't.

After a few tense seconds that seemed like hours, this critter decided to run 20 feet to the left. Our feet decided to move even quicker in reverse. I'm not sure if it was the sudden movement or the sound of stomping hooves that set our legs in motion. I bet we looked like the three stooges stumbling over each other in our hasty retreat!

The critter was a muskox. Don't worry, we knew it wasn't a bear. If you've never seen a muskox, just imagine a cross between a cow, Cousin It, and the Tarheel mascot - big, lots of long hair, and curly horns. I'll bet Trey had quite a shock when he rubbed his eyes and discovered that it wasn't a bush he had walked up to!

Our river journey began high in the mountains where the valley was less than a mile wide. Snowcapped mountains rose above the valley on either side. On a dayhike up one mountain, we encountered several herds of Dall sheep. Smaller, all-white cousins of the Bighorn sheep, these animals allowed us to pass within 50 feet of where they were munching on grass and lounging among the rocks.

August in Alaska is a good time to see the caribou migration. All together there are about 500,000 animals in the western arctic herd. They spend the summer on the North Slope and migrate through the Brooks Range mountains to spend winter in southern parts of Alaska.

We saw caribou moving steadily down the valley in small groups of up to a dozen animals. The antlers on the adult males were impressive, sometimes extending four feet or more above their heads. Caribou are the same animal as the reindeer of northern Europe. I kept looking for one with a red nose but never saw it.

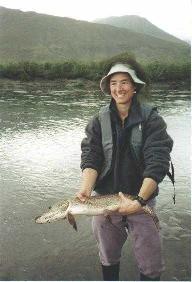

We also enjoyed sightings of golden eagles, huge swans, arctic foxes, marmots, and a 30" northern pike, which joined us for dinner one night.

About three days into the trip, the lead canoe rounded a bend and caught a brief glimpse of a mother grizzly and three cubs crossing the river.

Eventually we passed out of the mountainous part of the watershed and into a broad plain. As the river dropped into this plain, it cut its way through several layers of bedrock. The riverbed here was steeper, causing the water to flow faster and rougher. We encountered standing waves nearly two feet high. A strong headwind complicated the whole affair by blowing our canoes around and making us shout just to talk to our canoe partners.

Back home, the rough water would have been easy Class II fun. But in Alaska, the water temperature is a major concern. It was 37 degrees F; if we fell in, hypothermia would be a serious threat. We decided to keep our boats closer together in order to perform a rescue if needed.

As we rounded a bend beneath a high rock cliff, I noticed the splashing white of rougher water ahead. The water left of center looked smoother, so that's where I steered. In a few more seconds we saw why it looked smoother there. Flowing water always looks smooth as it drops over a ledge!

By then we were committed to our line. There was no way to stop or back up, so over the edge we went. At the bottom of the 3-foot drop the water swirled to the right. The swirl shoved the bow of our canoe to the side while the stern was still coming over the ledge. Can you picture what happened next? Swimming in Alaska!

My paddling partner fell completely out of the front of the canoe. I did an imitation of a rat scrambling for the high point on a sinking ship, but still managed to get wet up to my chest.

The canoe lay on its side for a few long moments before righting itself. I settled back down in the canoe, which was now full of water. Only the air in our gear bags kept it floating. Everything stayed in place thanks to our tie down straps. Somehow we even managed to hang on to our paddles.

The river rushed us downstream while I struggled to paddle our submarine towards shore. The adrenaline rush warmed me as I knelt in a tub of ice water. My partner was still hanging onto the side of the canoe, afraid to climb back in for fear of sinking the canoe. Paddling a canoe with a person hanging onto the side is a slow process.

I'm not sure if I even looked to see what happened to the other canoes, which had been right behind us. When I saw the ledge, my world shrank to about 10 feet in diameter. Anything beyond that became irrelevant.

When we reached calmer water, over half a mile downstream, I heard Trey yelling at me from shore. They made it through the big waves at the ledge with only 10 inches of water coming into their boat, not quite swamped. When they got close to shore, he jumped out of the canoe with the rescue rope and shouted to his father, "Get the raft to shore!" We had a good laugh later because his brain had reverted to his raft guiding days in the heat of the action.

Trey raced down the rocky bank after us, falling several times before he got within range with the rope. An experienced arm put the rope in my hands on the first throw and together we pulled the submarine to the safety of shore.

The riverbank looked like a yard sale with wet gear strewn everywhere. We quickly changed into dry clothes. We were lucky that it was a fairly nice afternoon. The stiff winds and colder temperatures we had on other days would have made hypothermia a sure thing. The fact that we were wearing insulating layers under full raingear at the time helped hold some heat in while we were in the water.

Now I can say I've been swimming in Alaska. We were much more cautious going around all the remaining bends in the river.

One day we rounded a bend and spotted another dark shape on the right bank about a mile down river. We'd seen lots of caribou by this point and expected this to be another one. As we got closer, we could tell it didn't have the long thin legs of a caribou. Perhaps it was another muskox.

Gene had his binoculars out and watched it as we floated closer. When it took a step, he knew it wasn't the waddle of a muskox. He fumbled with the binoculars as he tried to get his paddle raised straight up in the air, our sign for bear!

The water got a little rougher as we drew closer. There was a gravel bar in the middle of the river. Gene tried to steer his canoe next to it so he could stop and get a picture. Trey, in the back of Gene's canoe, was having nothing of it. He was shouting "Paddle! Paddle!"

I quit paddling and got my video camera out. Between the rough water, the wind, and my partner paddling furiously in the opposite direction, my shots came out looking like the alleged film of Bigfoot. He's there, you just have to chase him around the screen with your eyes.

At the closest, we were maybe 40 yards away. The bear was completely oblivious to us. We were downwind and he was intent on rooting around for whatever berries or critters he was after. I wished I had been able to get a better picture. But to this day, the others are still convinced that if the bear had seen us, he would have raced over in 2 seconds flat and enjoyed a nice lunch of paddlers, packed two to a can.

Despite the numerous rain showers we paddled through, the headwinds that sometimes blew us back upriver, and the mile-long portage across soggy tundra at the end, we all had a great time. We ate well, slept plenty, had loads of fresh air, and enjoyed some spectacular scenery. It frosted two nights, but the daytime temperatures were in the 40's and 50's most of the time. Experiencing such an adventure makes for wonderful memories and strong friendships.

Our goal of getting far away may not have succeeded as well as we had planned. Even though we were almost 4,000 miles from home, we discovered just how small this world can be. There was another group camped just upriver from us when we arrived. As they paddled by the next day, we asked them where they were from.

With a familiar southern accent they said, "Charlotte, North Carolina."

On the wall in the lodge/restaurant in Bettles there is a picture of a small plane, a 1940's Luscombe. The caption reads "Thanks for your help on my 1995 flight from Kitty Hawk to Pt. Barrow, AK and back." It was signed by Jim Zazas, of Carthage, NC.

As we waited for our flight back to Fairbanks, we chatted with a hunter just arriving in Bettles. Jim was his name. He's a retired schoolteacher. He lives on NC 93, just north of Sparta, NC. A little white house on the left. My friends and I pass by it several times a year on our way to go backpacking at Mt. Rogers in Virginia. Next time I go up, I'll have to stop by and ask Jim how his hunt went.

© Don Childrey 2000

The portage from hell!!!

The article above was published in the Montgomery Herald on 9-13-2000.

Related links:

- Map of the park. Our trip started in the western end of the park, west of Mt. Igikpak. Two-thirds of the distance we covered was outside the park in the Noatak National Preserve.

- Brooks Range Aviation. This is the outfitter who flew us from Bettles out to the Noatak River, and picked us up 12 days later!

Thanks for reading!

More pictures: